AN Introduction to Poetry, A complete online course, lectures

Introduction

Students often cringe at the idea of studying poetry. In our experience, they do so for two main reasons.

An Introduction to Poetry starts off where so many of our students start off, with the very misunderstandings they bring with them to the course. Having taught and tested the material in this course for more than ten years, we have accrued ample evidence that students—whether excited or dreadful about being in our class—almost always come to class with misconceptions that impede their understanding.

The two attitudes mentioned above can also be characterized this way.

“I hate poetry (and I don’t know why they’re making me study it).”

“I love poetry (and don’t want you to ruin it for me).”

To these statements, we respond: “Why do you love (or hate) poetry?” “What do you think poetry is?” And, “How do you know that the thing you love or hate is a poem?”

As for the lovers of poetry, very often these are students who confess that they write poems themselves, or that they used to write poems. They use poetry to express their emotions. Poetry is perhaps the art form people are most likely to feel entitled or equipped to practice without ever studying. But do these students who come to class loving poetry really know what it is they love—are they sure that what they really love is poetry. Often these students who love poetry don’t love any actual poems.

When they tell us they you shouldn’t have to study something meant for pleasure, we let them know they are right. You certainly can leave poetry at pleasure; there’s nothing wrong with that. You can eat food without studying nutrition, just on the basis of enjoyment. However if you take a nutrition class, you aren’t going to be able to get away with deciding what foods are good or bad based solely on taste. And if you take a class on nutrition you will get more out of eating food. Nor is it suitable in a college class merely to read poems and not also to study them. You wouldn’t take a class in music and expect merely to listen to songs for three hours a week or a class in auto mechanics and expect just to drive a lot of cool cars. And you won’t expect in a poetry class to read poem after poem without thinking in various ways, including technical ways, about what you are doing, why you are doing it, and how the poems you are studying work.

Poetry is perhaps the world’s oldest science as well as the world’s oldest art (yes, we tell them, poetry is also a science—a form of knowledge, a way of knowing). You don’t have to enjoy a poem to study it; you don’t have to study a poem to enjoy it. But if you enjoy poems, you will be motivated to study them, and if you study them, you will improve your enjoyment.

As for the haters, we tell them we don’t believe it’s possible to hate poetry. They may hate the fact that poems sometimes make them “feel dumb.” Of course they are not dumb. But it’s hard not to feel that way when, it seems, everyone around you is sharing a deep, meaningful experience of a poem while you’re scratching your head and praying no one will ask you what you think. If a student feels that way—and everybody does from time to time when learning something new and foreign, whether it’s poetry or French or cooking or car repair—we show them that it’s not poetry that is the problem, nor is it their intelligence. We assure them that once they learn how to read poems, they’ll see that they can’t hate them. Human beings cannot hate poetry any more than they can hate music. No one hates music. There are people who are indifferent to it. And you can be indifferent to poetry, we suppose. And nearly everyone dislikes particular styles of music or particular songs. And you can certainly dislike some styles of poetry, and if you don’t dislike some poems, you are not a very careful reader. But to the best of our knowledge all human beings respond to rhythm and—unless they are deaf—sound. And even deaf people respond to music.

So our complete course is designed first to get students over their impeding prejudices. Thus we spend the first two weeks mainly reading poems, listening to poets talk about what they do, and letting students react however they like. We respond to their comments with guiding questions that point them always back to the poems: “Why do you think the poem says that?” “What words are you looking at?” “What do you do with these other words?” We ask them to think first about what a poem says, not what it means: we ask them to read, not to interpret. (Student often get into trouble when the jump to interpretation without carefully reading the lines and the sentences of a poem.) Because this text has been designed for an online class, each chapter includes a video in which we invite students to watch us read poems in ways that respond to the theme of the particular unit or chapter.

After exploring for two chapters various ways of thinking of what a poem is, we draw students more deeply into the process of reading in our third chapter. We ask them to forget for a while that poems are historical documents created by human beings. Instead, we tell them to read poems without any help but a dictionary. We ask them to read ahistorically, the way the New Critics asked us all to read 70 or so years ago. We say, before you bring into the poem any apparatus that may lead you to feel comfortable with half understanding a poem, learn all that you can from the words alone.

Each following week is devoted to a theme or an issue. The earlier of these chapters explore in greater depth the things that often make it hard to understand poems. We devote a week for example to exploring how poems reference other poems in ways only someone deeply read in poetry is likely to recognize and another on ways that poetry reflects on itself and the question of what it is and what it’s for. We spend yet another week on figurative language and another on poetics. After this, we devote an entire week to the sonnet, as an example of how form works in poetry, and then we include in the next week a number of other forms—odes, elegies, villanelles, ballads, epics, and sestinas. (We don’t ask them to read entire epics.)

Having devoted the first half of the course mainly to reading and formal topics, we spend a week exploring the topic of the representation of women in poetry, from medieval lyrics to the late twentieth century, revealing a narrative that develops like a novel through time, as men represent women and women’s (mostly sexual) power and as women, first quietly and then much more vigorously, write back to that representation.

Having traced one topic over centuries, we look more closely at those centuries in the final weeks of the course. We start with the English Renaissance, the earliest period whose poems students can be expected to read without straining, before moving, in large hunks, through the Enlightenment, Romanticism and into the twentieth century, where the course ends. Here we can only manage to give a taste to the broad evolution of poetry through time. But by now the knowledge we’ve been accruing all term about what poetry is and how it works are placed in historical contexts that allow them to make better sense of what has been happening all along.

Although the text comes out of an online Introduction to Poetry, we have followed it closely in face-to-face classes as well. We have worked to develop a text that is easily adaptable. There is a theme to each chapter that makes it possible to consider it as a stand-alone unit. At the same time each may serve to build on what came before.

Acknowledgements: in addition to the hundreds of students whose experiences and reactions have shaped this text and the colleagues whose suggestions through the years have influenced our teaching of this material, including David Edward, Paula Delbonis-Platt, Kristina Lucas, Lynn Kilchenstein, and Cathy Eaton, we would like to acknowledge the help of a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Community College System of New Hampshire Humanities Collaborative in the development of this course. We also would like to express our special thanks to former New Hampshire Poet Laureate Alice B. Fogel for her kind permission to allow us to include recordings of her work made especially for this text.

What Is Poetry? When Is a Poem?

|

“In my view a good poem is one in

which the form of the verse and the joining of its parts seems light as a

shallow river flowing over its sandy bed.”

—BASHO (Translated by Lucien Stryk) |

Some

say a poem is a song or a prayer; it’s both controlled and uncontrollable, a

flight of the imagination or it comes from

a dream state. It is both inspiration

(breath & movement) and perspiration

(a poet’s practice of craft).

A

poem is a made thing. And, according to Ed Hirsch writing a poem “is a

soul-making activity . . . [p]oems communicate before they are understood and

the structure operates on, or inside, the reader even as the words infiltrate

the consciousness.

POETRY

AND MUSIC

Imagine

yourself driving down the road, listening to your favorite song, either singing

along or just grooving to the beat. Your passenger in the seat next to you

asks, innocently, “What does this song mean?” You stop; you think. It’s your

favorite song. But what can you say?

“I

dunno. I just like it.”

You are welcome to “just like it.” Who says you can’t like a song just because it feels good?

- Of course, we can ask what the song is about,

what it means, but we know we don’t have to ask in order to like it. Most

songs do have meaning. Even dumb songs have meaning. We know that.

- We also probably know that the

meaning of a song is not limited to the lyrics; a song expresses its

meaning through the lyrics and the music. We all

immediately understand that words like “I’ll love you always and forever”

have one meaning when they are sung to a tender, lilting, melody and a

very different meaning when they are shouted over screeching guitars.

- Poems

have a lot in common with music. Poems can be enjoyed for

their sound and rhythm alone; they can be appreciated for how they make us

feel without conscious consideration of meaning. They also have a meaning.

As with songs, the meaning of a poem

is never absolutely separate from the meaning of its sounds and rhythms—its

music. We don’t have drums and electric guitars and pianos; but rhythm and sound still carry

meaning, and, like poets, we readers can learn how this works.

Our most

fundamental job this semester is to discover how poems create meaning through language and rhythm and sound.

- Students sometimes cringe at

the idea of studying poetry. They fear that studying something meant for

enjoyment goes against its nature. Students think that poems, like songs, are

meant to be enjoyed. So leave it at that.

- You certainly can leave it at

that; there’s nothing wrong with leaving it at that. You can eat food

without studying nutrition just on the basis of enjoyment. However if you

take a nutrition class, you aren’t going to be able to get away with

deciding what foods are good or bad based solely on taste. Nor would it be

a suitable attitude to adopt in a college class merely to read poems and

not also to study them. You wouldn’t take a class in music and expect

merely to listen to songs for three hours a week or a class in auto

mechanics and expect just to drive a lot of different cars. And you won’t expect in a poetry class

to read poem after poem without thinking in various ways, including

technical ways, about what you are doing, why you are doing it, and how

the poems you are studying work.

- Nor is it contrary to the

nature of poetry to study it. Nor does it take the fun out of reading

poems. Poets themselves have all spent countless hours studying their

craft, its history and its methods, and are thrilled when readers

appreciate the technical innovations of their work.

- And serious readers of poetry

(and serious students of all the

arts) have always known that to fully appreciate an aesthetic object,

you need to study both the object itself and the history and mechanics of

the type it represents.

- Poetry is perhaps the world’s

oldest science and art (yes, there is a science of poetry). You don’t have to enjoy a poem to study

it; you don’t have to study a poem to enjoy it. But if you enjoy poems,

you will be motivated to study them, and if you study them, you will

improve your enjoyment.

Five

Myths That Make Poems Harder to Love

In

our more than 30 years of teaching poetry in colleges and universities, we’ve observed

that students tend to approach the subject from certain common half-truths or

misconceptions. We’ll call them myths. Although these myths are not true and not even compatible with

each other, a number of students believe all of them.

1) It’s all subjective: Some

students believe that poems have no real meanings at all. When they read a

poem, students may think, “I can think anything I want about the poem. It’s all

interpretation, and there are no right and wrong answers.” (We hear those

sentences many times a year. It’s a hard myth for some students to give up).

2) Poems are nothing but ideas that

rhyme: Some students insist that poetry is the practice of putting

“ideas” into rhyme. Some may think “the poem is all about what it says; the

rhyme is there just for fun.”

3) Poetry is just a form of self-expression:

Whatever students believe about the meaning of a poem and the relationship of the meaning to the sounds, many students

believe poetry is mainly about “expressing yourself” or, more specifically

about “expressing your emotions.” They may think that, “in poetry, poets simply

put what they feel onto paper in words.”

4) Poetry is all about how it makes

us feel. So it doesn’t matter what the poet might have thought about

what they were saying when writing the poem.

· One

student put it this way: “I would like to think that

although I’m unable to point to something

specific in the poem that gives me a particular feeling, it’s still a

reaction I get from reading the poem. And if my particular feeling is not what

the poet intended, well it’s just too bad. I feel something after reading a

particular poem, and I’m not totally wrong, because it’s my reaction to it.”

5) Poems give advice, mainly good

advice, about how to live. Students who understand that it’s possible

for a poem to say something then often assume that what a poem says can be

boiled down to simple wisdom or a cliché like: “Be yourself,” “Live life to the fullest,” or “Appreciate the small things.”

- You probably find yourself in

one or more of these places. This is where most students begin. You may be

glad to know that most Americans probably agree with you. Nonetheless, we must understand at the start that these are myths. There may be

an element of truth to some of them, and they are more false than true. As we study poetry this

semester, let’s work to overcome these myths and prejudices. And remember,

most Americans have never really studied poetry.

- If

you leave the class with any of these prejudices unqualified or untransformed,

something will have gone very wrong for you in your introduction to poetry. We

will be dealing in one way or another with each of these prejudices throughout

the term.

Now,

we’ll comment on each of the 5 myths in a preliminary way.

- These five myths are not just

common; they are understandable. It’s not hard to see why people who have

had only a slight association with poems would believe these things. They

are so pervasive that most people pluck them out of the air.

- And then they read some poems,

perhaps in high school English that they don’t understand. And since they

don’t understand the poetry, they assume they must not have any meaning—in

the ordinary sense.

- Or perhaps they are forced, in

class, to come up with a meaning for a poem they don’t really understand,

and therefore they decide that the poem just conveys some quasi-profound

sentiment we’ve known since our Sesame Street days.

- In fact, there is so much

going on in most poems that it’s easy to be confused by them. Of these

myths or prejudices, only the first one is absolute nonsense. Poems are never meaningless.

- Although some skill may be required

in understanding the ways that poetry works, and although people do often

debate the meaning of poems, poems (as

we’ll say several times and in more detail) are made out of sentences;

the sentences these poems are made of are English sentences with English

words in them.

- These

sentences follow the exact same grammatical rules as any written English

sentence and, although they do more than most sentences not found in

poems, they produce meaning in the same

way that English sentences always produce meaning.

- This bears repeating: there is no way of using language that

is exclusive to poetry. Not even rhythm and rhyme.

- We’ll see during the semester

that poetry uses language more intensely than normal for producing meaning

and thereby produces more meaning than a typical sentence such as the one

you are reading now.

- This does not negate the

grammar of the sentences or the meaning of the words. The concentration of

words makes poems more meaningful, not less.

Often, this concentration of words

along with the unique form of a poem can make poetry seem

more confusing and difficult. And it is because poems are often confusing (and

in rare cases deliberately confusing) that readers sometimes assume they don’t

really mean anything at all, or that there are no right and wrong answers.” (I

hear that sentence many times a year. It’s a hard myth for some students to

give up on.) Read this:

- The

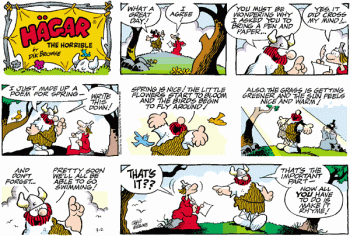

second myth—the “Hagar the Horrible” prejudice, that poems

put ideas into pretty sounding words—comes

from the fact that many poems use a range of sound and rhythmic devices

that appeal to readers in a visceral way, as music does.

- What we hope to understand,

in studying poetry, is that the “pretty sounding words” are not merely decorations on the meaning of a

well-written poem (nor is the music simply a decoration on the meaning of a good song). They are part of the meaning. You

cannot understand deeply what a poem is about unless you understand how the poem is saying what

it is saying or doing what it is doing. The words may sound

pretty, or they may sound deliberately ugly. However they sound, and the sounds are carefully chosen and

meaningful. They are not just decoration.

- The

third myth—that a poem is merely a poet’s expression of emotion—is

at best an oversimplification, and with the vast majority of poems, it’s

simply false. A poet is as free as

any writer to write about themselves or their emotions. Most poets do not. Poets aim

at common or even universal

experiences, not personal ones. So even if they do happen (as they

sometimes do) to write about their own lives or experiences, the point of

the poem is never in fact the experience of the poet.

- Although we don’t divorce

feeling or emotion from poetry, if a poet, (a human being like the rest of us), just wants to express

emotion, they probably have better ways of doing so than writing a poem.

The poet can yell or scream. They can punch a wall or a kick a cat. The

poet can sigh or cry or laugh, spit in someone’s eye or give someone a

big passionate kiss. Against these possibilities, saying something in

stanzas and meter and rhyme—a process which takes hours if not weeks or

months to do, much more time than anyone can sustain an emotion—seems a

pretty inefficient way to express emotion.

- Still,

this prejudice is the most pervasive of all.

The problem is not, then, that the prejudice or myth is absolutely false,

but that it is limited and misleading. If we hang on to it too tightly, it causes us to misread poems. In

fact, the importance of emotion varies greatly from poem to poem. Some

poems may wish primarily to produce an emotional effect. The vast

majority of poems also wish to produce a meaning effect as much as an

emotional effect. The emotion is

something you feel; the meaning is something you understand. It is the

reader’s not the poet’s emotion that matters.

- The

fourth myth—that all reactions are valid because they are reactions—is

impossible to deny. If you fall in love with a dog

because he bites you, no one can tell you haven’t fallen in love. We might

however question whether that was an appropriate reaction to a dog bite.

Of course all reactions are “right” insofar as they are reactions, but not

insofar as they are interpretations (or readings) of a particular poem.

And we hope that, whatever your reaction, you feel absolutely free to

announce it in the discussions.

- Still, not all reactions ultimately make sense in relation

to the poem. And once you’ve announced your response in this class, you’ll

also be asked to explain it. One may very well misunderstand a poem and

then respond to the misunderstanding. The student quoted above was convinced

that the poem she’d read was

about “rebirth.” Her reasoning was this: “Every life comes from death,

and with death comes life.” The problem was just this: the poem in

question was demonstrably not

about rebirth. (If you don’t understand Italian you might think all

Italian songs are love songs because the language is so pretty.) It was a

good reaction. It was a good defense of her reaction. But it was still

wrong.

o

Responses to and interpretations of poems

need to be grounded in the poem itself—in the words and the form the words make

on the page.

- The

fifth myth—that poems give advice—is different from the others

because it admits that poems have something to say. There is no law that

says a poem can’t give advice. And it’s often possible to turn an

observation into advice. But poems are

not about giving advice. Poems make observations and convey experiences. That’s

really all they do. We may wish to turn these observations and

experiences into advice. We are free to do that. But poems do not expect

us to do that. And in our experience it’s not a good idea. If we say,

“It’s very cold out,” you might decide, “I’d better stay in.” If we were

your fathers or mothers or lovers, we might want you to draw that

conclusion, to stay inside. If we were your poets, we would not care what

you did. We would merely hope that whatever you did, you did it in the

awareness that it’s very cold out. It is one of the most universally true

things you can say about poem: Poems do not give advice.

- You may still think

otherwise. You likely have read any number of rhyming texts that do give

advice—they circulate on the Internet pretty freely and we tend to call

them poems.[*] But

these texts are poems in only the most general sense of the word

poems

because they rhyme. Such trite and sentimental verses are quite

different from what we are studying. The poems like those in our course—poems

that dedicated artists write—explore and observe human life and human

experiences and aim at unique but representative moments. They attempt to say

what has never been said before, to say it fresh.

One of the reasons poetry is difficult is that it says new things or old things

in new ways. One way of attempting to understand—or pretending to

understand—what we don’t understand is to

force it to conform to something we do understand. The result often is to convert a unique and challenging observation

into comforting advice.

So

What Is Poetry, Really?

If

these myths or prejudices don’t tell us what we need to know about poetry, what

do we need to know?

- The two most common responses

we get from students regarding poetry are these:

1)

“I hate poetry.”

2)

“I love poetry.”

- The first is we’re sad to say,

far more common than the second. Presumably, since you have voluntarily

chosen to take this course, you will lean closer to response 2. This gets

us over one of the difficult humps in the road to a fuller understanding

and appreciation of poetry. But it does not necessarily get us to where we

need to be: a workable starting point for the study of poetry.

- When we get either response,

we like to find out if the sad or exuberant student has a clear idea of

what it is they love or hate. Students tend to find our follow up question

odd. Instead of asking, “Why do you love (or hate) poetry?” we prefer to

ask “What do you think poetry is?” Or, to ask it another way, “How do you

know that the thing you love or hate is a poem?”

- We

don’t believe it’s possible to hate poetry. People

who say they hate poetry usually

struggle with their inability to understand particular poems. They hate

the fact that poems sometimes make them “feel dumb.” Of course they are

not dumb. But it’s hard not to feel that way when, it seems, everyone

around you is sharing a deep, meaningful experience of a poetic lyric

while you’re scratching your head and praying no one will ask you what you

think.

- If you do feel that way—and

everybody does from time to time when learning something new and foreign,

whether it’s poetry or French or cooking or car repair—you must first of all understand that it’s

probably not poetry that is the problem, nor is it your intelligence; it’s

unfamiliarity in general and the need to learn. Once you learn how to

read poems, you’ll see that you can’t possibly hate them. Human beings

cannot hate poetry any more than they can hate music. No one hates music.

There are people who are indifferent to it. And you can be indifferent to

poetry, we suppose. And nearly everyone dislikes particular styles of

music or particular songs. And you can certainly dislike some styles of

poetry, and if you don’t dislike some poems, you are not a very careful

reader. But to the best of our knowledge all human beings respond to

rhythm and—unless they are deaf—sound. Even deaf people respond to music.

- So

the most trimmed down answer we can give to our question “What is a poem?”

is this: A poem is a work of resonant,

sensual language that makes a unique observation about life.

Final

Words

That’s

not an entirely satisfactory definition. So here are some more thoughts.

- Poetry happens when resonance

and sensuality combine. This means that “poetry” is a feature

(or function) of language in general and is not in any way restricted to

poems. Poetry is however made manifest in the form and content of

poems.

- True, not everything that

looks like a poem is necessarily poetry; some “poems” may be merely verse

(simple ideas that use meter or rhyme merely for decoration). And sensual,

resonant language is not restricted to poems. One may find it in

conversation, prose writing, cereal packages—anywhere language is deployed

(we call such instances “poetic,” as in, “she speaks so poetically about

playing tennis that it makes you want to take up the sport).

- While poetry may appear in

these other places, poems are where poetry must always be. Poems and poetry are defined in

relation to one another.

LECTURE #2: How to Read a Poem (and Maybe Even Fall in

Love with Poetry)

“The reader of poetry

is a kind of pilgrim setting out, setting forth. . . . Reading poetry is an adventure in renewal, a

creative act, a perpetual beginning, a rebirth of wonder.” —Edward Hirsch.

Are Poems “Open to Interpretation”?

That depends on what you mean by “open for interpretation.”

Picture this: A

politician says, “I won’t support this bill because it will hurt the middle

class.” You hear that and maybe you think, “Yeah, right. You won’t support the

bill because if you do the bozos who elected you won’t vote for you next time,

and you’ll lose your cushy job.”

Or this: You ask

a professor a simple question about quadratic equations and she spends half an

hour tracing the origin of mathematics through the middle ages all the way back

to ancient Greece. So you think (but are too polite to say), “This is about

math, not about you. Stop showing off.”

What do these incidents have in common? In each case, someone interpreted what someone said to

mean something other than or more than what it seemed to mean.

We could multiply examples of this all day. You may have

come into this class thinking that poetry (or literature) is unusual in using

language to mean more than they seem to say. But in fact language itself

can always mean more than what it seems to mean. We are all interpreters of

language. Hearing what is not said is something we learn to do from a young

age, and it’s a skill we use every day.

To the extent that poems are made of sentences, and all

sentences, even this one, are to some degree “open for interpretation,” so are

poem. And yet...

- Many

students enter this course with a profound misunderstanding of the issue

of interpretation with regards to art in general and poetry in particular.

Somewhere along the way, you may have picked up on the idea that poems are

“completely open to

interpretation.” But what would

be the point of that?

- What

do we mean when we say a poem is “open

for interpretation”?

- Two

things:

- First, all language, even this

paragraph, is by its very nature open

to different understandings. (We’ll explore this further in the next

lecture.)

- Second, poets (who are artists) often

exploit the inherent ambiguities, playfulness, and multiple meanings of

language in order to create their art. They do this on purpose, with

specific intentions, in order to create multiple meanings and to enrich

their art.

- So, yes, understood correctly, poems

are “open for interpretation. But

- Not all interpretations are equal. And

- While no interpretation is complete

- Some

interpretations are defensible (which is a better word than “right”), and

- Some are not.

We can be more specific: Here

are a few problems poems bring to inexperienced readers and ways to overcome

them.

1)

The

poem conveys a difficult idea.

Difficulty if this type in poetry is

not essentially different than difficulty in prose. Even experienced

readers of philosophy sometimes read the

prose of a profound philosopher and feel their brains oozing toward their

ear canals. Sophisticated, subtle or specialized language is often difficult.

This is not, however, the most common problem in poetry. Solution: Don’t try to

figure it out on your own. Ask questions.

2)

The language is old or arcane.

The words may be unfamiliar or

seem familiar because they’re unusual or have specialized meanings. Solution: All you need to do if you don’t know a word

or if you think you know a word but don’t understand how it’s being used is

look in a dictionary. Readers use

dictionaries.

3)

A poem’s syntax (word order) is

unconventional or a sentence is unusually complex.

·

In some poems, perhaps in order to get the

rhyming words in the right position, poets, at certain times in history, felt

an urgent need to rearrange sentences (in imitation of Latin), a big problem in English poems of the

Eighteenth-Century.

o The line “What dire offense from amorous

causes springs,” puts the verb, oddly, at the end. In ordinary everyday

English (even in the 18th century, when the line was written) it

would read: “What dire offense springs from amorous causes.”

·

In other poems, sentences are rearranged in

order to surprise the reader, something that poetry often seeks to do. In other words, poets seek to create

possibilities of meaning not available otherwise. And poets use syntax (as

well as line ending) to play with

readers’ expectations and stretch the many meaningful possibilities of

language.

·

Some sentences

are particularly complicated. You

may get lost.

·

Solution:

ignore the ends of lines. Read the poem as though it were prose and put the

words back in their normal order. Look for the subject or verb; you may need to

separate a main clause from a subordinate clause. (Warning: This may destroy

all the “poetry” in the poem, so make sure to put it back together and read it

again when you’re done.) And always ask

for help when you need to.

4)

The sounds (or music) in a poem are a

distraction.

·

They can be. Poetry tends toward concentrated and lyrical or musical language.

Therefore, you’ll need to enhance your powers of concentration. This takes

practice. Just keep reading.

·

Solution:

Practice.

Of course, there are

other reasons why poems sometimes seem difficult. However, the difficulty

of poems is usually less than it seems. Poetry is a specialized use of

language. It’s the art of language. Some artists

use sticks or metal to make sculpture; some use pigments to make paintings or sounds

to make music; poetry uses words to make art. It’s therefore a highly

self-conscious use of language. And it’s

in constant search for new subjects and new materials: words. Learning poetry

is something like learning an always-changing dialect of your own language. A

guide can help. But persistence helps more.

Try not to forget as you go through this material that the

most important thing that could happen in this class would be for you to learn to

enjoy poetry (and dare we say fall in love with it?).

But, since the enjoyment of poetry is one of those things

that cannot be tested, we’ll have to lower our sights a bit and try to help you

get a better understanding of poetry. If at the end of this unit, you can reply

to the doubters in defense of poetry, we’ll have accomplished something. We

will console ourselves in the knowledge that a better understanding of poetry may lead to an actual enjoyment of it.

Some things you need

to know:

The study of poetry is work. It involves

- Careful

reading

- Analysis

- Testing.

What we’ve said so far is sound general advice for getting

the meaning (in the ordinary sense) out of poems. But let’s put you in this

very concrete situation: You’re sitting down in front of a poem you’ve been

asked to write about for this class. What do you do?

Learning to read a new poem

is like learning to play a new song a guitar. So try this: Decide before you begin that you are going to read every poem at least three times. It’s important

no matter how long the poem is.

Reading poems out loud is best. Read the poem the first time

straight through, pronouncing each word. You’re not looking for meaning or

sounds. You’re just familiarizing yourself with the words, allowing them to

bend back the grass in your brain so that they’ll be easier to walk through the

next time.

Read the second time for sound. Concentrate on how the sounds fall.

Hit the rhymes, pick up on the rhythms, notice (but don’t dwell on) any interesting

use of sounds in the

poem.

Read slowly and smoothly. If you stumble through the poem the

second time, read it again and again until you get to the point where you no longer stumble over sound.

Read the poem the third time

for meaning. When you are reading for meaning, keep in mind two things.

§ First (we say it again), the vast majority of poems are written in

grammatically correct sentences. It will help you a lot if you know how to

recognize a verb, a noun, and how to find them. And, if you know how to

distinguish a subject from an object, you’re well on your way. If you go

through the sentence from beginning to end and don’t understand it, look for

the verb, find its subject and its object. Don’t confuse line ends with

sentence ends or even with natural pauses. You’ll be tempted to pause at line

endings. Realize that the pause may not

come where it would come if the same sentence were presented as prose. Often

the sense keeps going past the end of lines. It’s good practice to try to paraphrase

the sentences of the poem one at a time.

§

Second,

it’s nearly always possible to see the poem

as a story. So look for it. Even poems not generally considered to be

narrative poems tell or suggest a story. Most poems have at least some of the

basic elements of a story: characters, dramatic

situation, setting, action. Ask yourself what story the poem seems to tell. As with most stories, a poem is likely to

come to us in two distinct voices: the voice of the poet and the voice of the

speaker of the poem (when we are talking about fiction, we use the terms

“author” and “narrator”). Most students do not realize that the speaker of the

poem is not the same as the author of the poem. And sometimes it’s true that

this distinction does not matter. But in most cases, a poem is spoken by an

unnamed “voice” created by the author for the particular purpose of the poem.

The easiest way to show this is with an example.

Look at these stanzas from a poem about discovering a snake

in the grass:

A narrow fellow in the grass

Occasionally rides;

You may have met him—did you not

His notice sudden is,

He likes a boggy acre,

A floor too cool for corn,

But when a boy and barefoot,

I more than once at noon

Have passed, I thought, a whiplash,

Unbraiding in the sun,

When stooping to secure it,

It wrinkled and was gone.

I’ve never met this fellow,

Attended or alone,

Without a tighter breathing,

And zero at the bone.[†]

This poem, by Emily Dickinson, relays the experience of a

boy who was scared when he stooped down to pick up what he thought was the lash

of a whip only to see it slither away. Dickinson

was never a boy and may never have had the experience she writes about. Why she

decided to narrate the poem from a boy’s point of view is something we can

discuss. When we discuss the poem, we typically refer to the poet or voice(s)

as the speaker or narrator in the poem.

However, what she does

shows us is that we should not automatically assume that a poem or the facts it contains are autobiographical. If there is

more than one speaker or voice in a poem then it’s important to hear all the voices.

- If

you think the poem is a story and recognize the speaker (or narrator), and if you can paraphrase each of the

sentences, you’ll have a very good handle on the verbal meaning of a poem.

- Don’t panic if this doesn’t work.

Perhaps you’ve missed something—like an obscure meaning of a word, and the

issue may not be yours at all. It may be that the poem resists this

approach. This is when you need a guide.

- Poems

were originally intended as communal, not individual, objects. And they

are still best read in a community. In this class, as soon as you are

stuck, it’s time to post. Get on the appropriate discussion and write

about what happened when you read the poem.

Remember, while meaning (in the ordinary sense) is hardly

ever the primary element in strong poetry, it’s always there. Any poem that

simply puts the music at the service of the meaning is likely to be inferior

for that reason. Language in which meaning is primary is plentiful enough. It’s

simply not the case with poetry. In

poetry the music itself is inseparable from the meaning.

Verbal meaning is important, and often is necessary for a

reader to be able to paraphrase a poem. But verbal meaning is never the whole. In good poems, musical meaning

is not secondary. And poems exist that cannot be paraphrased. So when we think

about what a poem is doing, we need to think about the music in addition to (or

as part of) the meaning of a poem.

This really is not a strange concept. If I scream “I love

you” through gritted teeth, the words won’t mean the same thing they mean if I

say them softly on my knees handing you flowers. The meaning is not in the

words alone.

Lecture #3: Poetry’s Poetry Period: Reading

Ahistorically

1. What Is Ahistorical Reading?

Poetry has always been

poetry. Sort of. Everything changes. In history, magic transformed into

science. Alchemy became chemistry. Natural philosophy became geology and

physics. Poetry too has changed. But it has not changed as radically as those

other disciplines.

We can treat poetry as though

it is one thing and that it has always been the same thing. And that makes

sense because poetry’s fundamental job of exploring and understanding what it

means to be human has stayed pretty consistent. Maybe that’s because we human

beings have always been more or less the same. Certainly there is, at least,

part of us that has always been the same.

In the course of this term,

we will spend a lot of time following the changes in poetry over time. But for

this week, we want to ignore those differences and think of all poems as just

poems. We’ll treat a poem by Shakespeare the same way we treat one by Donald

Hall.

We will assume that, despite changes,

there is an unchanging element in poetry that responds to whatever is

unchanging in ourselves. In other words, we can decide that we’ve always used

poetry the same way or gotten essentially the same thing out of poetry no

matter what clothes it wears, and so, in a sense, that poetry has always been

poetry.

What is “timeless” in human

beings is sometimes called “human nature,” and when human nature is mentioned,

it has always been considered our essence, and sometimes capturing human nature

in words has been described as the goal of poetry (and in fact of all literature).

It is natural in humans to fear death, for example, and to love, to fall in love,

to hate, to seek justice, honor, dignity, power, and revenge; it is human

nature to ask questions about existence and to seek answers. And all of these

things are also subjects and purposes of poetry. Humans have presumably also

always found comfort in meaning and in music. Poetry has provided these things too,

always in response to these needs.

If in some ways people are

always the same and poetry is always the same, then we don’t necessarily need

to appeal to anything outside of a poem in order to understand it. We just need

to understand the meaning of the words and of the sentences. Reading a poem

without reference to when it was written or who wrote it means reading a poem ahistorically.

Students often find the idea

of reading a poem ahistorically puzzling. Why wouldn’t you want to ask the poet

what she meant to say when she wrote the poem? And why would you not want to

look at the historical context in which a poem was written? If a poem is about

slavery, wouldn’t you want to know if the poet was a slave?

While it’s true that knowing

history and biography can be helpful in reading a poem, we don’t need to know

these things to understand most poems. And there are a number of reasons why

seeking that knowledge may not be the best place to start.

1)

As the poet Paul

Muldoon says, “The idea that poetry

comes from beyond oneself is vital.” In other words, according to Muldoon (and most

poets) the writer is not the origin of his poems. Poets generally agree that they

don’t know where poems come from. It could be the muse, it could be nature, it

could be the unconscious, it could just be language. Poet in an important sense

are therefore readers of their own poems. So they don’t necessarily have any

better authority than anyone else to explain all the meanings of their work. They

are good and useful readers. But that is all they are. We don’t need their

opinions.

2)

History can

mislead as well as clarify. At every moment in history millions of things are

happening. Each one of them is something you could use to help read a poem. But

how do you know which are relevant or how any one thing is relevant to

understanding a poem? If you choose the wrong one, you will probably go in the

wrong direction in your interpretation. Until

you have gone as far as you can into understanding a poem without invoking

history, it’s usually best not to invoke history at all.

3)

If you do need to

call up history, the history you need to call up is probably already in the

poem. If for example the fact that the author was a slave is relevant to the

understanding of the poem, that fact will probably be revealed in the poem

itself. We’ll see specific examples this when we look at poems in the video

lecture. So it’s a good strategy to look very carefully at the words of the

poem before looking for anything outside the poem.

We do want to make it clear: history

and biography can be useful. But they become useful after you have read the poem as thoroughly as you can without them.

They are not essential for understanding poems. Start with the poem itself. Most of the time you’ll find that this

is enough for a sound, satisfying understanding of a poem.

As we said above, certain

features of poetry make it possible to think of poems as always and everywhere

the same thing. What are those things? We must start with one that seems so

obvious it might seem not worth mentioning: the word “poetry” itself and its related

words (poet, poem, poetics). William Shakespeare in the sixteenth century may

not have been doing exactly the same thing in many respects that Donald Hall in

the twenty-first century did when he wrote a poem, but certainly he wasn’t

doing something entirely different either. And both poets were aware of the

fact that they were writing a thing they called a poem, making a work of art

out of written words. The word itself carries a certain degree of sameness.

The second and third thing

may also seem obvious: the look and sound. Although it is not quite universal,

the vast majority of poems are defined to a great extent by the line—that

string of words that starts on the left side of the page and never seems to

make it all the way to the right side. Nearly all poems look different on the

page from the way non-poems look.[‡]

You can usually recognize poems just by looking at them. While this does not

absolutely define poetry, it is one nearly universal feature of poems. Most

poems also use the resources of rhythm and sound in such a way that you can

recognize a text as a poem even if you are not looking at the words on the page

but just hearing them read.

We’ve already pointed to two

other features as well: subject and function. While it’s certainly true that

poetry does not always and everywhere focus on the same subjects and doesn’t

always do exactly the same thing, it’s equally true that certain subjects and

functions persist over time. We’ve always had love poems. We’ve always had

patriotic poems. We’ve always had poems about death and war and religion. And poems

have always helped us understand and invited us into emotional experiences.

Poetry has also always explored and observed the human and natural world. It has always tried to find

answers to the question of what it means to be human and it has always worked to

give readers or listeners a particular type of intellectual/musical pleasure. In

last week’s lectures we called poetry “sensual language.” This is useful. But,

like all the qualities mentioned so far, it cannot be absolutely defining. All

language (which is always in some sense material even if it is restricted to

your own private brainwaves) is to some degree sensual, and the best prose may

sometimes exploit the sensuality of language better than some poetry, but along

with form and subject, the concept of sensuality certainly helps us get an

understanding of the things that throughout history have continued to be true

about poetry.

When we talk about the poetry

ahistorically, we must talk about poetry’s relationship to language in general,

its particular ways of using language. It has often been said of poetry that it

uses language most fully: The Romantic-era poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge famously

called poetry, “The best words in the best order.” More recently it has been

said that poetry is “language at its best: Poets use its full potential, using

more of it and using it to better advantage than we usually do.” Of course not

all actual poems manage this. But the best poems and poets do. And it is always

the goal. One thing that makes something a poem is the striving for the fullest

use of language. Poetry is language with a musical (sensual) side. It’s

language that calls attention to itself as language, and that has a tendency

toward creating an experience. Poems use language to create or express meaning,

but the poem is not about that meaning itself as much as they are about a

created experience.

This is how the language of

poetry is different from the language of science for example. If, in science, you explain Einstein’s theory

of relativity well, you have done justice to the theory. There’s no need to

read Einstein’s version. If you explain it better than Einstein did, then

losing Einstein’s own explanation would be no loss at all. With science the point of the explanation is the understanding of the theory

because the language of science is all about its meaning; the point is not

the language is used to explain it. It’s not even the E=MC2, even

though the formula is elegant. Other letters tied to the concepts of energy, mass,

and the speed of light would serve just as well; for the sake of explanation, a

sentence would do the same job as the mathematical equation.

A poem is different. If you

explain a poem, you have done some service to the poem. But you have not got

the poem itself. You can only hope to “have” the poem by reading or

experiencing the poem. A poem, unlike a

scientific treatise, is never exclusively about the thing it says, its

meaning. It’s always also about the way it says it. If you say the same thing

in different words you have a different thing.

So when we read a poem, what

we want is the experience the poem creates. And to get that, worrying about the

history of the poem and the intention of the poet can be distracting. That is

why, to start with, we are happy to ignore these distractions.

2. So does this mean that when we read a poem we are

free to interpret it anyway we like?

Let’s be careful here. What

does it mean to “interpret” a poem (or anything else)? To interpret is, most

basically, to read and understand. We tend to use the word “interpret” for

things whose understanding is not obvious or that different people are likely

to understand differently. “Interpretation” is not just something we do to

poems or to art. Certainly poems require interpretation. But so does every

sentence that you read. And the process of interpretation is not fundamentally

different whether the sentence is written in a poem or an essay or a news article

or your own private journal. It’s true that poetry takes greater advantage of

the material aspects of language (its sounds and rhythms and its look on a page)

than other forms of writing. And it’s also true that poems are more likely to

use elaborate figures of speech than other forms of writing. But all types of

writing not only use figures of speech, but they use exactly the same types

that poems use—metaphor, simile, personification, metonymy, etc. You use these

and interpret these same figures every day without thinking. Moreover, all

types of language, even science, use rhythm and sound as well. So the question of interpretation is a

question about language and not a question about poetry. The best poems may

use all the parts of language to create meaning. But even so, there is nothing

about the language of poems that is true only in poems. There’s literally nothing

unique about the way the poems use language.

It’s true that everyone is,

to some degree, different from everyone else. It’s also true that all people

are to a large degree the same. We will all bring our unique perspectives to

everything we do—whether that’s poetry or algebra. But if we didn’t also bring

our sameness, communication would be impossible. In both poetry and math our

uniqueness can be both a hindrance and a help. One way we are not unique is

that we all speak the same language, English. And in English (as in all

languages) words have established, accepted meanings that we can’t ignore if we

wish to talk to one another. That’s as true in poems as it is in any other form

of language. This means that it is possible to have a common understanding of a

poem—of what a poem is saying. On its most fundamental level, the understanding

of almost any poem is common (that is, shared) to all readers and the author of

the poem.

In fact it is not only

possible but in most situations necessary to have a shared understanding of the

meaning of poem, of what, in the most obvious way, it is saying, in order to interpret it. We must share

as much as we can in order to open ourselves to where we can legitimately differ.

So let’s be clear: There are right answers and there are wrong

answers when it comes to poems. But this doesn’t mean there’s only one

right answer. In fact there is never only one right answer if by “right” we

mean a complete or perfect or final or absolute answer. We can say a lot of

true things about any poem, just as we can say a lot of true things about a

dog. And we can always understand any poem better no matter how well we

understand it now, just as we can always understand ourselves or friends or our

lovers better. This is something we have to understand: although no answer is

final or complete, it is possible to

misunderstand a poem. And it is even possible for two people to

misunderstand a poem in the same way. Let’s look at an example.

This poem is by Emily

Dickinson:

I like to see it

lap the miles,

And lick the valleys up,

And stop to feed itself at tanks;

And then, prodigious, step

Around a pile of

mountains,

And, supercilious, peer

In shanties by the sides of roads;

And then a quarry pare

To fit its sides,

and crawl between,

Complaining all the while

In horrid, hooting stanza;

Then chase itself down hill

And neigh like

Boanerges;

Then, punctual as a star,

Stop—docile and omnipotent—

At its own stable door.

If we ask, “what is the poet

describing,” you might reasonably respond, “a horse.” And you might explain

that horses live in stables and they neigh and they feed at tanks—sort of. But if

we tell you in fact she’s writing about not a horse but a train, you might see

that much more of the poem makes sense. Things you ignored because you didn’t

know how to fit them into your horse interpretation now make sense. Real horses

don’t neigh “like Boanerges” (sons of thunder). And they don’t really drink

from tanks. They drink from troughs. And a horse cannot as easily be said to

chase itself downhill as a train can. In fact “train” makes “sense of every

detail of the poem, whereas horse makes sense with only some. In short if you

said, “this poem is about a horse,” your interpretation would be

understandable, but it would be wrong.

What this means is that in an

important sense what a poem says is not

usually “open for interpretation.” But as for what it means, that’s different. We all need to agree about the basic

meaning of the sentences. What the poem itself uses these sentences to mean (in

a bigger sense) is not limited to what the sentences mean on their surface. We

can talk as long as we like about that deeper meaning. Is Dickinson celebrating

progress? Is there any sense of irony in her celebration of a train as though

it were a living thing? (Is she really saying she doesn’t like trains?) What

does it mean to call a train “docile and omnipotent”? If she likes to see it

“lap the miles” does she like the sounds it makes too (“complain… in horrid,

hooting stanza”)? Knowing what a poem is saying does not end the interpretation.

This is where interpretation starts. Knowing what a poem is saying is just a

matter of plain reading. Missing or

skipping this step often causes students problems.

And what a poem is saying is

not a riddle. If you don’t understand it immediately, there are various reasons

for that, depending on the poem. The grammar of the sentences may be too

complex and hard for you to follow. You may not know all the words. You may

think you know the words but not realize these words are being used in a

special or rare sense. You may not realize that a certain image is meant figuratively.

And on and on. These problems can be easily fixed. If you don’t understand a

poem, this is not a judgment on you or the poem. All you have to do is explore—which

means, as a start, asking questions about it. Since the poem is not a riddle,

the question of what it is saying is not what we are after in this class. There

is no secret we’re trying to uncover. We may need to paraphrase the poem to

show that we understand it. But that is where the discussion begins, not where

it ends.

In almost every case, if you

are confused about what a poem is saying, you will not be able to interpret it.

And in almost every case, it’s easy to show you what a poem is saying. As with

this Dickinson poem, the misunderstanding will probably be easily fixed.

Does this mean that all poems

are paraphrasable? No. Some poets play with language in ways that make it

impossible to come up with an adequate paraphrase. But these are rare. A paraphrase

tells you what the poem is saying. But the meaning of the poem in a more

profound sense is in what it is doing, not what it’s telling you, but what experience it is offering you. If a

poem could be understood by its paraphrase, then there would be no point

writing the poem. Confusing a poem with its paraphrase is like confusing a

picture of a bird with an actual bird. You cannot experience an eagle by

looking at a picture of an eagle or even a filmed eagle. And you cannot

experience a poem through reading a paraphrase. But sometimes that paraphrase

offers you a way into a poem.

Poetic Language

Perhaps you’ve heard the phrase, “he (or she) was just being poetic.” It’s a phrase you

wouldn’t be surprised to hear after someone utters some flowery description of

a sunrise or a snowstorm. It describes a use of language that is perhaps

pretty, but also empty, something that meaninglessly ornate. It’s an

unfortunate use of the word. Authentic poetic language is very different.

We will call “poetic language,” that language which is most

closely associated with poetry. It is also called “figurative language.” It is

opposed to so-called “literal” language. Understood in the context of actual

poetry, poetic language is not nice-sounding words that have no real meaning. It

is the fullest possible use of language. Poets pack the absolute maximum of meaning

(in every sense of the word) into every part of the poem. This does sometimes

make poems hard to understand, and that may mislead a hasty person to think

there is nothing to understand. In other words, one of the reasons poetry

sometimes seems empty is that it is so full.

It’s important to understand first that poems are not made

entirely of what is properly called “poetic” language. Poems don’t use only

figurative and never literal language. As I’ve said already: the language of

poetry is not essentially different from the language of everyday life. That

means two things: it means that everything we do when we use language outside

of poem, we also do in poems. It also means that everything we do in poems, we

also do in everyday language. All of the “devices” that we properly associate

with poetic language are also used regularly in everyday language, spoken or written,

and not just by people who have a vast or specialized education or a particular

facility with language. “Poetic language” is used by everyone, including you

and your three-year old brother. It’s not overstating the case to say that poetry is a part of language itself and that

poems are merely the most concentrated expressions of language’s inherent poetry.

Poets are more conscious of the the poetry already in language and more deliberate

in their use of it. Poems heighten or intensify certain ordinary ways of using

language. We might say that poems put the emphasis on different aspects of

language—including the language we call figurative. But they still don’t do

anything that we don’t already do every day when we speak.

And yet poems don’t usually feel like everyday language.

Everyday language is usually easy to understand. And poems often are not.

Everyday language tends to say exactly what it means—or at least tries to.

Poems don’t seem to do that. We come back again to a question we addressed in

Lecture #1: Why don’t poems just say what they mean? We began to answer this

question when we said that poems are not merely trying to say something. They

are also trying to do (or be) something. But that answer is incomplete. We did

not explain how poems use language to

do things. We will begin to answer to that question here. We know that poems

use sound (such as rhyme), and rhythm and lines. We’ll talk about these other

things in later lectures. Here we will be thinking about how poems use

figurative language to create meaning and experiences.

Literal and Figurative

Language

As I said, so-called figurative language is usually opposed

to what is called literal language. Literal language is language that says

exactly and directly what it means; it is language without figures. Figurative

language then, as it is usually understood, is language that takes a kind of roundabout

path to its meaning. It uses various devices to get you where it wants you to

go. That might lead you to believe that figurative language is harder to

understand than literal language, and that we should use literal language

whenever possible. But that’s not quite true. In everyday usage, figurative

language is usually used to help us understand what a literal statement cannot.

Its most important job is to make difficult things easier to understand. It is also

used this way in poetry.

For example, I might say to a child, “A country is like a

school with a president instead of a principal.” Here I’m using the figure of speech known as analogy to bring a new concept to a

listener.

Figurative language is also used to give more weight or

authority to a statement. I’m using figurative language if I say, “According to

the White House” instead of “According to the President.” This figure is known

as metonymy, the substitution of one

thing for something closely associated with it.

If I say, “That was the funniest thing in the whole

universe,” or “Hitler wasn’t very nice to the Jews,” I’m using yet other kinds

of figurative language and again getting more out of the words than a literal

statement could. The first statement is an example of hyperbole (high-PER-bow-lee,

also called exaggeration). The second is the opposite, litotes (lie-TOE-tease, or understatement).

We use many kinds of figurative language every day because

we want to do more than just state facts. We use this sort of language all the

time, usually without knowing we are doing so. So the good news is that you do

understand figurative language; you understand it so naturally that you

probably do not even notice that you are interpreting such figures as irony,

metaphor, simile, hyperbole, litotes, personification,

apostrophe, metonymy, or synecdoche. So the first problem is just

learning to recognize and name things you are already unconsciously familiar

with. The second is to understand how these figures are being used in particular

poems. Poems are likely to use figurative language more often and in more

nuanced ways than we use it in everyday language.

That’s the bad news. Poems don’t always use metaphor to make

hard things easier to understand, for example. Poems may use metaphor to make

seemingly-simple things no-longer simple. Remember, poems want you not just to

understand but to experience the world in new ways. But we are so accustomed to

seeing things however we see them that the work of a poet is quite difficult.

We resist without even knowing we are resisting. And we may often fail to see

figurative language in a poem for what it is. And even the most experienced

readers of poems argue sometimes about what counts as a metaphor or a symbol in

a poem and about what a particular figure means. This is something to love

about poetry. You get to enter and participate in an ongoing conversation. But

to do that, you need to ground yourself in the figures. You need to be able to

name and point to them.

You might wonder how it is that experienced readers of poems

can argue about what counts as a particular figure in a particular poem. This

is because the very ideas of “literal” and “figurative” are not as clear as we

might like to think they are.

Again, according to the standard definitions, figurative

language is language that states its meaning indirectly. It represents one

thing by means of another thing. The “president” is called “The White House”;

the ocean is called a “pond.” At the

same time, literal language is language that states its meaning directly. The

president is called the president, and the ocean is called the ocean.

But that already creates a problem. In one sense, all

language is figurative. The distinction between “literal” and “figurative”

language does not easily correspond to the facts. Unless the word “ocean” is

something you could be tempted to swim on, we have to admit that the word ocean

is something used to represent an object, and is therefore not literally

literal. The word “ocean” is not the ocean. It stands for or represents

the idea of the ocean. And representing one thing by another thing is, by

definition, what figurative language does.

When we are talking about

“literal” language we are merely separating off from all language that part

which seems to be the most direct or transparent, which is to say the most

commonly or habitually used representation of a given idea. (If I say, “What is

that?” and point to the ocean, most people will say, “the ocean.” So we call

that literal.)

So, there is no such thing

as an absolutely non-figurative language. This means that you can never absolutely

guarantee that any statement, no matter how literal it seems, is not also

figurative. Take this simple sentence: “He fell down the stairs.” You’ll

probably want to say, “that’s obviously literal.” But is it? For it to be literal

it has to describe an event that actually happened. Outside of a known context

there’s no way to decide whether the sentence is literal or figurative or both

(yes, a sentence can be both at the same time). The sentence “He fell down the

stairs” could describe what it felt like for him to have his heart broken, or it

may describe the effects of getting a demotion at work: “He went to the boss

thinking he was going to get a promotion. He thought he was going up in the

company. Instead, he fell down the stairs.”

Compare some other common figurative expressions that at

first glance sound literal: “he was on fire,” “he bought the farm,” “he got

burned,” and “he lost his way.”

So the difference between literal and figurative language has

nothing to do with the words themselves. It has to do entirely with the way the

words are used or understood in a specific context. The same sentence which in

one context, or read one way, would be literal, in another context or read

another way would be figurative. Because one of the most natural things to do

with words is use them to represent (to represent either “things” or

“concepts”) it will never be absolutely possible to prevent any words from

being taken figuratively even if it was not meant that way (this is true in

everyday language as well as poetry, but it doesn’t usually cause any confusion

in everyday language).

The poet Marianne Moore, a great baseball fan, once

described a new young poet by saying, “He looks good—on paper.” The effect of

the sentence depends up on the reader’s understanding that poems are literally

written on paper and that, figuratively speaking, “he looks good on paper”

means “the information we have on him tells us he should be good, but we still

have to see him perform.”

The boundary between literal and figurative isn’t always

clear.

We also need to say a few words about the distinction we

made above, that literal language is “more direct” than figurative. This may

not even be true either. So-called “literal” statements can only be considered

more direct in regard to the most superficial meaning of the word “meaning,”

that is, only in regard to the referential content of a statement. But recall

what we have been saying all along: that “zeroing in on a meaning” is never

more than one possibility of language. And it’s never the sole purpose of a

poem. Figurative language is therefore not necessarily “roundabout.” Figurative

language is often more direct than “literal” language. This is because in a

poem the thing we are directing our

attention at is an emotion or an experience rather than a meaning. If I say “Tom

Brady was ‘on fire,’” I’m getting closer to the emotional truth of the event

than if I say “Tom Brady played exceptionally well last night.” I am also getting

closer to the truth of the experience of watching him this way than I would be

if I listed his accomplishments. I’m giving an indication of what it was like

to watch him play, what it may have been like for him to play. And if that’s

what I want to do, the figurative language does it better—more directly.

Everything is guided by purpose, by what the poem is doing.

Compare these three examples: 1) She felt sad.

2) She felt as though she’d just lost her

best friend.

3) She turned

away and looked out the window. The world outside became blurry.

Let us say that example 1)

is literal, i.e. that it refers to an actual woman or girl who really feels

sad. In that case the statement is referentially true, but it carries little

emotional content; example 2) would then be figurative. You will notice that it

also captures somewhat more of the case. If true, it is more accurate than

example 1) because its figure reproduces more of the emotional quality of the

sadness than any purely literal statement could. But because the figure is a

cliché, it still manages less emotional content than a careful writer probably

desires. Example 3) is the most emotionally effective. It is the most effective

because it is both literal and figurative. Turning away and looking out the

window are actions that suggest more meaning than the actions alone convey. And

the world did not really become blurry. Really, she started to cry.

We can say then that we need

both figurative and literal language because they do different jobs. A writer,

whether she is a writer of prose or poetry, fiction or nonfiction, will choose

the method of expression according to the job that needs to be done.

Now that we have an

understanding of what poetic, or figurative language is, let’s define more

precisely the most common examples so that you can practice identifying them

when you come across them. They are: metaphor, simile, metonymy, synecdoche,

hyperbole, litotes, irony, apostrophe, symbol, personification

Here are some examples:

Metaphor—a figure

of speech in which one thing (which usually is easy to understand) stands for

another thing (which is often more abstract). You’ll see that the metaphor works a

little differently in each of the three examples below. In the first case the

metaphor has an obvious, simple relationship to what it refers to. In

Thou ill-formed offspring

of my feeble brain,

Who after birth didst by

my side remain…

If you do not read carefully,

you may think

On the other hand, a

metaphor may have a less clear relationship between its two parts (its image and referent, more formally known as its vehicle and its tenor).

In

Blake’s painting

of his tiger.

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or I

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

You might also notice that

within the overall metaphor of the tiger, there are other metaphors such as

“burning bright.” “Burning bright” compares our metaphorical tiger to a fire.”

But why is the tiger burning? When you read the poem, you will see that this

tiger was made with a hammer and chain in a furnace. The metaphor makes a tiger

the creation of a blacksmith (the blacksmith being a metaphor for God). This is

not how “literal” tigers are made. Why has

Still other metaphors may be

impossible to pin down precisely. Both of the figures mentioned so far evoke

emotion or feeling as well as meaning. But it is possible to take a figure so far

into the emotional that it loses all sense of the intellectual meaning, as some

claim T.S. Eliot does in this image from a poem not on our syllabus, “The Love

Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”:

The yellow fog that rubs

its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs

its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the

corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools

that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the

soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace,

made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it as a

soft October night,

Curled once around the

house, and fell asleep.

It’s clear that the poet is

comparing fog to a cat (this is an implied

metaphor because the cat is invoked without ever being named). The

“catness” of fog is however far less obvious than the fearful power of blacksmith/God

is to a tiger or the mother to child relationship of an author for her book. Moreover,

this fog-cat metaphor is stretched out to such an absurd length that it begins

to lose sense. We learn very much less about fog by comparing it to a cat than

we learn about books by comparing them to children or about God by comparing

him to a blacksmith.

But the difficulties we may

have with the cat-fog metaphor doesn’t mean that the poet has failed. In the

context of the poem it is clear that the metaphor is meant to reveal more about

the state of mind of the title character than about the catness of fog.

We’ve barely begun to

discuss the intricacies of metaphor. But that will be enough for now. We can